Arrogance, incompetence, and Big Government: Why “Minnesota has a fraud problem”

Mo' government money mo' problems

Back in 1973, when Time magazine ran a story titled “The Good Life in Minnesota” and put our state’s governor, Wendell Anderson, on the cover, the article stated: “Politics is almost unnaturally clean.” Author Lance Morrow went on to write: “No patronage, virtually no corruption.”

Once you have scooped your jaw off the floor, you’ll agree that no honest person would write that about Minnesota today. Yesterday, my colleague Bill Glahn noted the outgoing U.S. Attorney for Minnesota, Andy Luger’s, comment that “Minnesota has a fraud problem.” Bill assiduously tracks the known frauds in the state which, under the Walz Administration, now total $543 million, or $95 for every Minnesotan. “No other states have had the kinds of problems we’ve had with government fraud,” Luger points out.

Why is Minnesota, once a beacon of clean government, now, apparently, a wide open money trench for any chancer who fancies helping him or herself to some of your hard earned cash?

Arrogance

Part of it is the attitude of the state government to your heard earned cash. Quite simply, they don’t regard it as something you earned, they have taken, and of which they are obliged to be careful custodians. Increasingly, they seem to view it as their reward for allowing you to be governed by them.

The recent case of Rep. Biana Virnig (DFL) exemplifies this. She got Minnesota’s taxpayers – that’s you, dear reader – to pay her legal fees in a private workplace dispute, a dispute which saw her pocket a payout of $108,224.54. This was all legal: all nine DFL members of the House Rules Committee voted to approve the payment. You paid so that she could get paid.

Incompetence

Another reason Minnesota’s state government is such an easy mark for those on the make is the sheer incompetence of a good number of its staff.

A new Minnesota law seeks to regulate political speech including making it illegal to use AI to “mislead” voters. Lawyers from the Hamilton Lincoln Law Institute and the Upper Midwest Law Center are, quite rightly, challenging the law on First Amendment grounds. The Attorney General’s office under Keith Ellison is defending the law and is bringing in expensive testimony to aid its case. How is that going? The Minnesota Reformer reports:

A Stanford misinformation expert has admitted he used artificial intelligence to draft a court document that contained multiple fake citations about AI.

…

[Stanford’s Jeff] Hancock billed the state of Minnesota $600 an hour for his services. The Attorney General’s Office said in a new filing that “Professor Hancock believes that the AI-hallucinated citations likely occurred when he was using ChatGPT-4o to assist with the drafting of the declaration,” and that he “did not intend to mislead the Court or counsel by including the AI-hallucinated citations in his declaration.”

The AG’s office also writes that it was not aware of the fake citations until the opposing lawyers filed their motion.

I do not suggest that this is fraudulent. But when the state government is paying a guy $600 an hour to argue that AI might mislead voters and his testimony includes stuff totally invented by AI, someone somewhere isn’t doing their due diligence.

Big Government

Another reason that taxpayer dollars in possession of the state government are such an easy target is that there are now so darned many of them. In 2024, General Fund Spending in Minnesota totaled 8.2% of the state’s total Personal Income, the highest share since at least 1998.

This week, as an example, the Minnesota Reformer – which, along with Bill Glahn, is about the best source of news on this subject – reported on problems relating to the K-12 Education Credit. This is a state tax credit for low-income families for tutoring services. It was increased in 2023, the Reformer reports:

The bill (HF915) expanded the tax credit from $1,000 to $1,500 per child and more than doubled the income threshold to $70,000, with higher earners eligible for a smaller credit. The bill also tied the income threshold to inflation, so it may increase every year.

In the event, it seems that a good number of the people who signed up for schemes related to this expanded credit have been provided with poor quality services for which they have been charged thousands of dollars. While this may not be fraudulent, it is certainly not an optimal use of taxpayer’s dollars.

Last year, in an article titled “The best way to cut government waste is to cut government spending,” I noted that the economist Milton Friedman explained back in 1980, in his classic book Free to Choose:

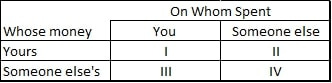

When you spend, you may spend your own money or someone else’s; and you may spend for the benefit of yourself or someone else. Combining these two pairs of alternatives gives four possibilities summarized in the following simple table:

Category I in the table refers to your spending your own money on yourself. You shop in a supermarket, for example. You clearly have a strong incentive both to economize and to get as much value as you can for each dollar you do spend.

Category II refers to your spending your own money on someone else. You shop for Christmas or birthday presents. You have the same incentive to economize as in Category I but not the same incentive to get full value for your money, at least as judged by the tastes of the recipient. You will, of course, want to get something the recipient will like—provided that it also makes the right impression and does not take too much time and effort. (If, indeed, your main objective were to enable the recipient to get as much value as possible per dollar, you would give him cash, converting your Category II spending to Category I spending by him.)

Category III refers to your spending someone else’s money on yourself—lunching on an expense account, for instance. You have no strong incentive to keep down the cost of the lunch, but you do have a strong incentive to get your money’s worth.

Category IV refers to your spending someone else’s money on still another person. You are paying for someone else’s lunch out of an expense account. You have little incentive either to economize or to try to get your guest the lunch that he will value most highly. However, if you are having lunch with him, so that the lunch is a mixture of Category III and Category IV, you do have a strong incentive to satisfy your own tastes at the sacrifice of his, if necessary.

…

Legislators vote to spend someone else’s money. The voters who elect the legislators are in one sense voting to spend their own money on themselves, but not in the direct sense of Category I spending. The connection between the taxes any individual pays and the spending he votes for is exceedingly loose. In practice, voters, like legislators, are inclined to regard someone else as paying for the programs the legislator votes for directly and the voter votes for indirectly. Bureaucrats who administer the programs are also spending someone else’s money. Little wonder that the amount spent explodes.

The bureaucrats spend someone else’s money on someone else. Only human kindness, not the much stronger and more dependable spur of self-interest, assures that they will spend the money in the way most beneficial to the recipients. Hence the wastefulness and ineffectiveness of the spending.

But that is not all. The lure of getting someone else’s money is strong. Many, including the bureaucrats administering the programs, will try to get it for themselves rather than have it go to someone else. The temptation to engage in corruption, to cheat, is strong and will not always be resisted or frustrated.

We have seen this clearly in Minnesota in recent years. Cases which are outright fraudulent, like Feeding Our Future, or, at best, grossly inefficient uses of taxpayer funds, like the K-12 credit controversy, arise when state government suddenly switches on the money hose and starts spraying it around. As I wrote last year:

Government wastes money because it isn’t in anyone’s interests, strongly enough, at least, for government not to waste it. If you want less money wasted, funnel less of it through the hands of the government. The only really effective way to reduce government waste is to reduce government spending.

What is true of wasteful spending is true of fraudulent spending.

Over to you, Governor Walz

Back in the state following his failed run for Vice President, Governor Walz is finally turning his attention to Minnesota’s fraud problem. “This pisses me off unlike anything else,” Walz told the Star Tribune. “They’re stealing from us … You’ve got to increase the penalty on these crimes. These are crimes against children, in my opinion.”

But, as my colleague Bill Walsh and I noted in June:

For all this government activity in response to COVID-19, Walz still managed to oversee the largest COVID fraud scheme in the country, with $250 million stolen. Millions more have been wasted in other fraud schemes throughout his time in office, but no one has been fired or held accountable.

Let us hope that this latest statement genuinely represents the governor’s attitudes. A good indication will be whether heads finally start rolling at any of the government agencies which have overseen the explosion of Minnesota’s “fraud problem.”