Minnesota loses residents of all age groups and incomes over $25,000 annually to other parts of the country

Migration, again

Net domestic migration — whether more people are moving to Minnesota from other parts of the United States than are moving from it to other parts of the United States — is a touchy subject. When the Star Tribune ran an op ed of mine back in 2020 titled “Migration out of Minnesota is on the rise” — an admittedly dry recitation of official data — Bob Collins, formerly of MPR’s NewsCut blog, took to Twitter to invoke the Ku Klux Klan.

If, by contrast, you think these matters can be debated sensibly, then the data are the best place to start.

Is Minnesota losing people?

When I began writing about this phenomenon, it was often hard to get people to take it seriously. That was understandable. In 2019, for example, Census Bureau data record that Minnesota saw a net inflow of 65 people from the rest of the United States.

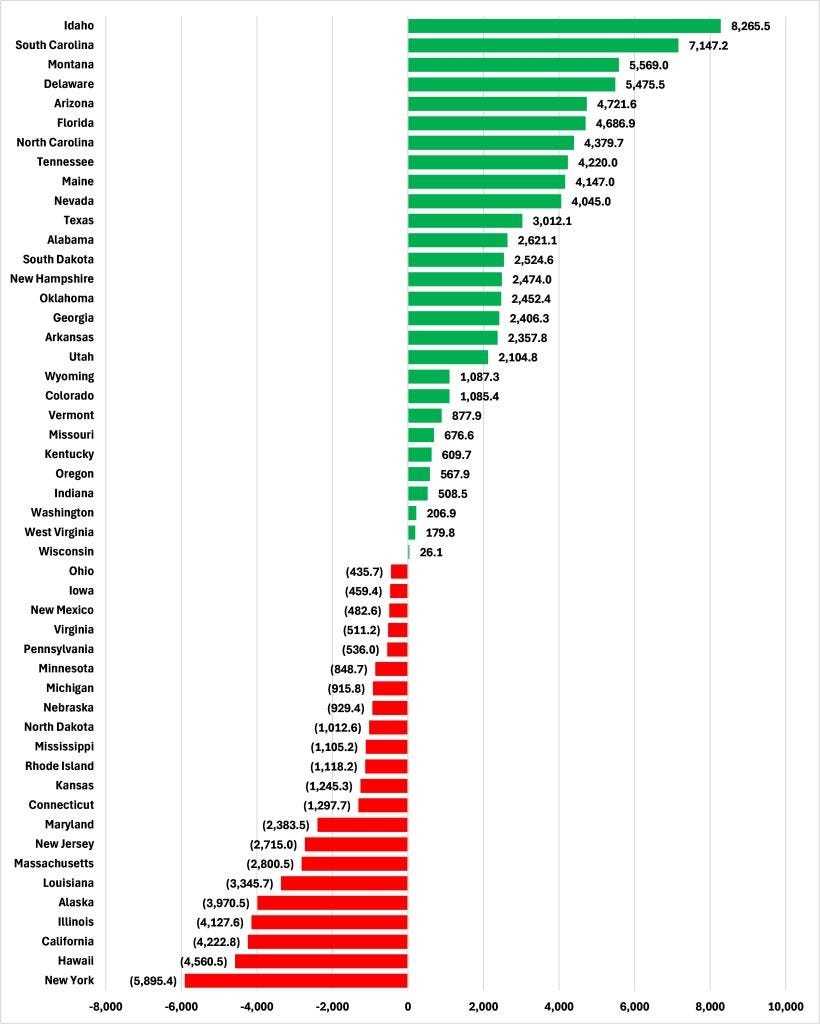

But that was the last year that we recorded a net inflow and our state has suffered a net loss of residents to the rest of the United States in every year since. Since 2019, Census Bureau data show, Minnesota has lost a net 47,865 residents to other parts of the United States which, as a rate per 100,000 of its 2019 population, ranks worse than in 33 out 50 states, as Figure 1 shows.

Figure 1: Total net domestic migration 2019-2024 per 100,000 of the 2019 population

Who are we losing?

We can dig a little deeper into this phenomenon.

The Internal Revenue Service (IRS) records the ages and incomes of the primary taxpayers in a household as they move — or don’t — around the country. This data is available up to 2021-2022.

Figure 2 shows the breakdown of Minnesota’s net domestic migrant flows by age. We see that, contra the common narrative that our domestic emigrants are older folks seeking sunnier climes, Minnesota actually lost residents, on net, between 2019-2020 and 2021-2022, in every single age category.

Figure 2: Net migration of individuals to/from Minnesota by age of primary taxpayer, 2019-2020 to 2021-2022

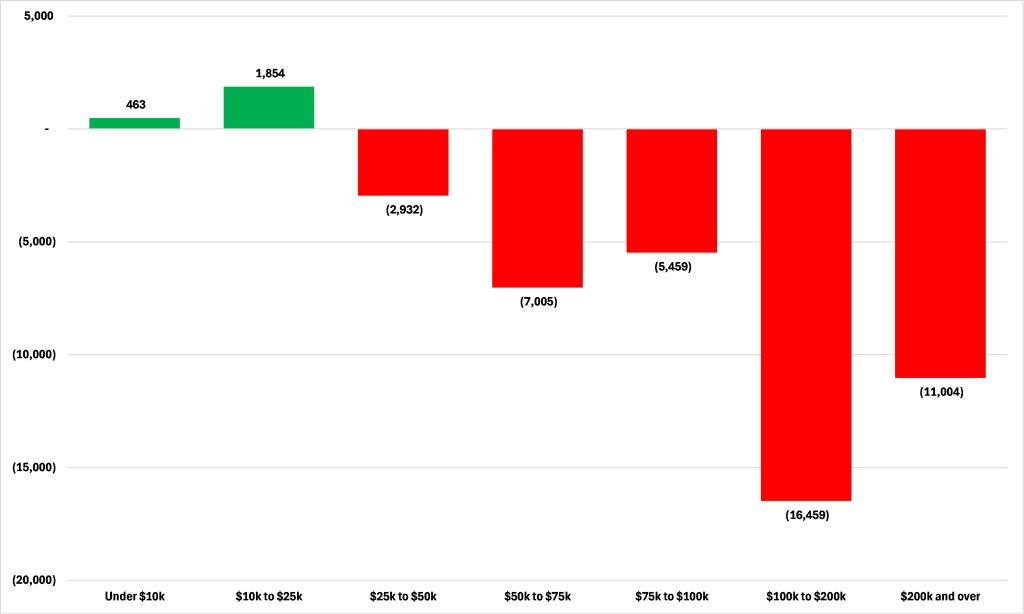

This pattern isn’t repeated if we look at the breakdown of Minnesota’s net domestic migrant flows by income. As Figure 3 shows, since 2019-2020, Minnesota actually gained residents, on net, in the income categories below $25,000 annually, but lost them in every income category above that. It is sometimes said that Minnesota’s emigrants are the rich fleeing high state taxes — as though that isn’t a problem — but the data show that, in fact, we record net losses of even middle class Minnesotans.

Figure 3: Net migration of individuals to/from Minnesota by income of primary taxpayer, 2019-2020 to 2021-2022

Where are they going?

If we are losing Minnesotans of all ages and of incomes above $25,000 annually, where are they going?

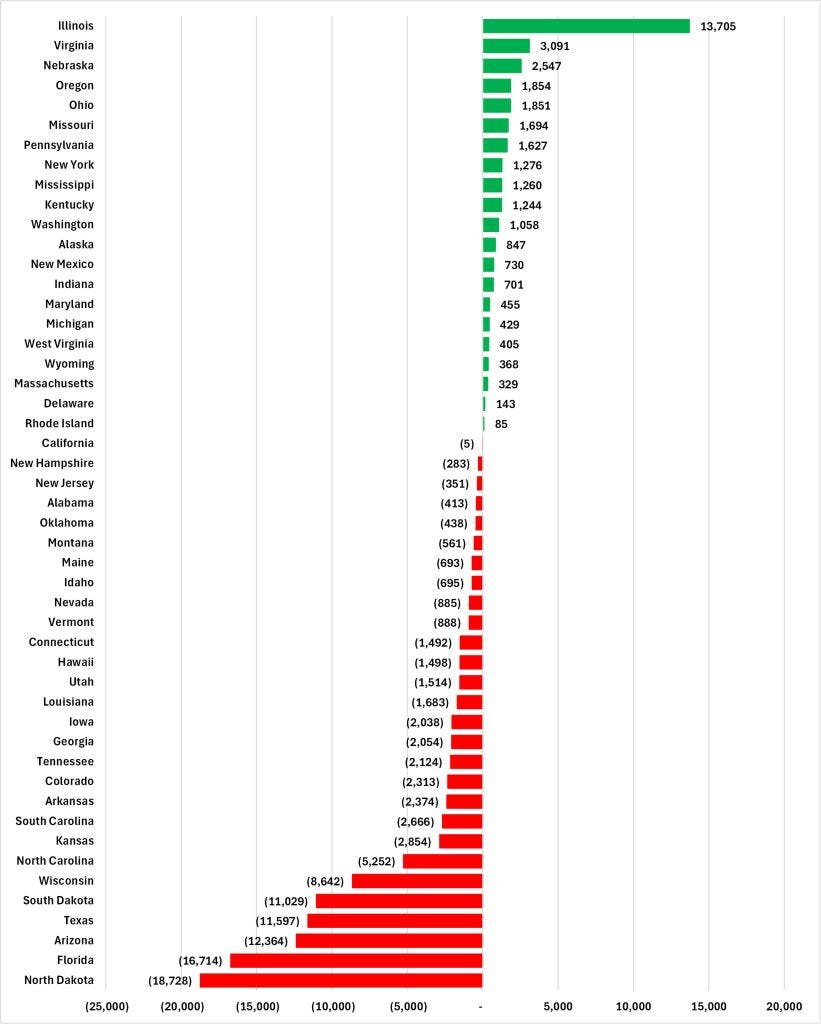

Once again, we can turn to Census Bureau data to answer this question. Figure 4 shows the net domestic flow between Minnesota and the other 49 states from 2019 to 2023, with data from 2020 absent. We see that Illinois has been, by far, our state’s leading source of domestic migrants, sending more than four times the amount the next biggest source, Virginia, did. At the other end of the scale, we see that the leading destinations are our neighbors and states which have either low — Arizona — or no — Texas and Florida — state income taxes. Probably, someone will call these “retirement” states, but look again at Figure 2; Minnesota isn’t just losing old folks.

Figure 4: Minnesota’s net state-to-state migration flows, 2019, 2021-2023

Why are people moving?

This is, perhaps, the key question, and the answer is “lots of reasons.” In a 2023 article, the Minnesota Reformer argued that:

…tax rates are far from the only factor affecting interstate migration decisions, and many economists say the link between taxes and moving is overstated: “Grossly exaggerated,” in the words of Michael Mazerov of the Center on Budget and Policy Priorities, a left-leaning think tank. Researchers have found that costs of living, job opportunities, recreation, crime and weather and climate have a major influence on where people move.

I’d agree that a number of factors are involved, but I don’t see how one can honestly conclude that “many economists say the link between taxes and moving is overstated” based on a quote from someone at “a left-leaning think tank”. At the time, I referred the author of that article to:

…this paper by economists Henrik Kleven, Camille Landais, Mathilde Muñoz, and Stefanie Stantcheva that: “review[s] a growing empirical literature on the effects of personal taxation on the geographic mobility of people and discuss[es] its policy implications” and finds that: “There is growing evidence that taxes can affect the geographic location of people both within and across countries. This migration channel creates another efficiency cost of taxation with which policymakers need to contend when setting tax policy.” More specifically: “This body of work has shown that certain segments of the labor market, especially high-income workers and professions with little location-specific human capital, may be quite responsive to taxes in their location decisions.”

As I concluded back then:

There certainly are more factors than just taxes that drive people’s location decisions. But a state government cannot control some of these factors, such as “weather and climate”, so it needs to focus on the factors it can control. And that brings us back to, among other things, the taxes it levies.

That is still the case.